Making and doing re-presentation with marginalised people

On this page the author explores re-presentation through the creation of a picture book with marginalised people. She reflects on the problematic that is ‘representation’ and about her on-ground engagement with and supervision by the people who are the ‘us’ in the text.

By Leonie Norrington

Australian fiction and non-fiction is saturated with negative and patronising representations of Aboriginal people. Since the 1970s post-colonial thought has moderated broad-based racial prejudice, however, the representations of ‘homeless’ Aboriginal people continues to be derogatory and negative.

Australian fiction and non-fiction is saturated with negative and patronising representations of Aboriginal people. Since the 1970s post-colonial thought has moderated broad-based racial prejudice, however, the representations of ‘homeless’ Aboriginal people continues to be derogatory and negative.

This object attempts a re-presentation of the stereotypical character of the ‘homeless Indigenous’ person. However, is it possible to represent another without the epistemic violence of speaking for, knowing/describing or translating for?

At the core of the multiplicity that is representation is the functional difference between the sharing of self (presentation) and the constructed interpretation of and offering up of another (representation). Adding a hyphen (re-presentation) works to destabilize the notion of objective reality in representation. However, re-presentation also allows for ‘presenting again’ in different ways that might trouble the initial representation. Created in collaboration with the ‘us’ in the narrative, this object hopes to re-present the normality the represented themselves wish to offer. Does this ‘going on together’ enable those who don’t write in English the ability to ‘self-present’ in a venue that is restricted to those who can narrate in English and the Western literary form?

The collaboration process

Taking a Ground-up research approach (Christie 2013) I visited the groups of people who live along the Nightcliff foreshore in Darwin. I stood outside the camps and waited for someone to come and invite me in. Some days they ignored me so I knew it was not a good day for talking. I only speak Kriol and English so each time I met with a group someone took over the role of translating language into Kriol. In the beginning I was speaking to new people and had to introduce myself each time, but after a few weeks, word got around and people knew what I was doing and were excited to meet and work with me.

Taking a Ground-up research approach (Christie 2013) I visited the groups of people who live along the Nightcliff foreshore in Darwin. I stood outside the camps and waited for someone to come and invite me in. Some days they ignored me so I knew it was not a good day for talking. I only speak Kriol and English so each time I met with a group someone took over the role of translating language into Kriol. In the beginning I was speaking to new people and had to introduce myself each time, but after a few weeks, word got around and people knew what I was doing and were excited to meet and work with me.

I explained that I wanted to create a picture book about them so that the rest of the community might get to know them as people and not be so negative and prejudiced.

They quickly made it clear to me that they weren’t the slightest bit interested or concerned by what the local media or the community were saying about them. As far as they were concerned they were perfectly within their rights to be where they were.

‘My people have been coming to this place for thousands of years. I’m right. They can’t kick me [out]. I can stay. My Grandfather’s father and his brothers come here in dugout canoes to collect their wives.’

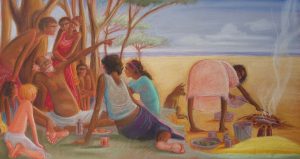

However, they were very keen to work with me on a picture book about people like themselves so that they could teach the broader community about belonging and being, properly on this land. They understood themselves as not on the margins of any society but as people in place with connections to the ancient past and the future; people with valuable knowledge and experience that could be useful to the broader society.

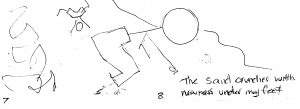

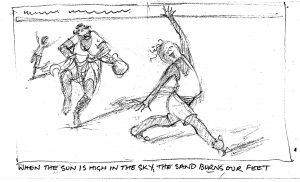

I worked with the different groups to create a storyboard. My stick figures gave them hours of laughter. I thought this figure was someone crouching down, but they interpreted as someone going to the toilet. ‘He can’t go there! He should go somewhere’ (somewhere more private where people can’t see him).

I worked with the different groups to create a storyboard. My stick figures gave them hours of laughter. I thought this figure was someone crouching down, but they interpreted as someone going to the toilet. ‘He can’t go there! He should go somewhere’ (somewhere more private where people can’t see him).

‘Father’s country will feed you every time,’ one old man said. ‘But mother’s country you have to ask.’ He wanted to show that people should ask the land to feed them ‘not just expect. That’s not the right way.’ So, ‘Uncle Tobias sends the silver lure far out to sea to call the fish in’.

We spent days talking about the old man’s name. He ended up being called Tobias because as a ‘bible’ name they thought it would show the reader that the person was mission-educated, and would hint at the terrible legacy of the Stolen Generation.

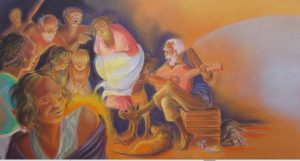

I did not want to show them drinking alcohol but most people said, ‘This is our life. We drink, we laugh, we sing and fight.’ So, Auntie Ruby has ‘a hospital towel around her because her dress is torn.’

I did not want to show them drinking alcohol but most people said, ‘This is our life. We drink, we laugh, we sing and fight.’ So, Auntie Ruby has ‘a hospital towel around her because her dress is torn.’

A subject most people came to over and over was their legitimacy; how their historical ties with this place afforded them legitimate camping rights here. So ‘Uncle Tobias tells story of the olden days when all his family came to fish this place.’

Negotiating with publishers was very complicated. Normally an author would write a text and sell it to a publisher. The publisher decides on the illustrator and the interpretation of the text. However, if the people I was working were to keep control of how they were presented, they needed to be able to veto the illustrations.

It was difficult to find a publisher willing to agree to these almost treasonous terms. Likewise, the illustrator was horrified when I showed her that I (the author) had created a storyboard. However, once I explained people’s need to control the representations of themselves, she agreed to draw up some roughs based on the story board and to listen and respond to feedback.

I took the roughs back to the people at the beach. Some images they were delighted with straight away, taking the images and keeping them.

Other images they laughed at, and criticised heartily, ‘Look out, she got white fella legs,’ (too fat around the ankles and shins). When Auntie Ruby is bending over helping the kids find food in the sand, her back is too curved. (whitefella way). Old ladies (properly) bend from the hips with a straight back. Also her breasts didn’t hang down like a proper woman, they were ‘bra kind’ (held up in a bra).

Some people were concerned about Auntie Ruby running holding her skirt up, showing her knees because it was a bit immodest and potentially dangerous for her if someone took offense. Her age was discussed in detail. Had she been a younger woman it would be more dangerous for her to run in this way. In the end they decided to let it stay like that to show that this older woman was a bit naughty and unconventional.

Throughout the process I brought up the issue of copyright and authorship. But people said that this ‘picture book’ way of telling stories was a ‘whitefella’ way. They had their own way to tell these stories, a way that was ‘whole’ (including story, song, art, dance) not ‘part’.

The final book was a loved and treasured item. Most people asked me to send copies home to family but some kept it in their camp so show and talk about. I never found one of the picture books abandoned but that doesn’t mean that they weren’t used to start a fire if the need arose. The book’s longevity in the camps among people who know the story already was not necessary.

Leonie Norrington is the author of fiction and non-fiction. .www.leonienorrington.com.au She is interested in how people use language and story to bridge difference or to make statements about their separateness. Leonie is writing a pre-colonial novel under the supervision of Indigenous Elders as part of a PhD at Charles Darwin University.